**************************************************************************************************************************

President’s Message

by Marvin Dolgay

I have always been a proud Canadian. When I was young, my father was a member of the folk singing group, The Travellers, and when they adapted and recorded the Canadian version of “This Land Is Your Land”, this was, perhaps, where it all started for me. But there was more to my understanding of what it means to be Canadian than just a laundry list of geographical points on a map, and the pride that is instilled with “This Land’s” mountains, forests and lakes.

For me, declaring that I was a Canadian meant that I represented a value system of fairness, inclusiveness, social responsibility, and the ability to care for the needs of all our citizens; in addition, our success and quality of life was defined not only by our wealth, but also by the value we placed on the human experience. I grew up understanding that these fundamental values crossed all political lines and because of that, these values were always at the heart of declaring that I am a Canadian.

When I look back at the incredible accomplishments that the Screen Composers Guild of Canada (SCGC) has achieved this year, I also take great pride in the fact that the same value system described above defines the culture of our guild and how we are approaching our representation moving forward.

This year, the SCGC board has set its number one priority of focus as: “work that advocates and promotes the value of Screen Composers to communities outside of ours, with the goal of improving their (the screen composers) ability to achieve and maintain fair and sustainable compensation and working conditions.”

The words “fair” and “value” stated in this priority support both the principle and the understanding that all stakeholders have a place in the value chain of our industry. With the fair distribution of the revenues generated by our efforts, we can ensure and maintain a sustainable and healthy industrial, and (dare I say), cultural ecosystem.

To that end, we have embarked on a few initiatives this year that will set the table to advocate for the fair value of composers and all music creators as new models of production and distribution are evolving.

One of the initiatives to further this priority was the recent ratification of a Framework Alliance Agreement between the Directors Guild of Canada (DGC) and the SCGC.

This alliance, while maintaining the ongoing independence of the SCGC and our ability to serve our unique community, as well as our certification under the Federal Status of the Artist Act, will give SCGC members an infrastructure to enable them to create and negotiate a collective bargaining agreement with our independent producer clients at the CMPA. I strongly believe that defining rates and working conditions will prove to be a win-win for both sides of the table in order to stabilize budgets and eliminate confusion when hiring a composer.

I would like to publicly acknowledge how thrilled we are to be so welcomed into the DGC family. This alliance is already bearing fruit as we build closer ties and understandings with our fellow filmmakers on how to create together a better product and better work flows.

I’m glad to see that our industry at large is finally admitting that the digital era is not coming but it is actually here and that it is indeed a game changer for us all. With this new normal starting to make its way into our day-to-day realities, business models to maintain fair value for creators must be addressed on a more global stage.

With that, I am very proud to say that at the World Creators Summit in Washington in early June, I signed a founding charter document on behalf of the SCGC, along with the Songwriters Association of Canada, the Songwriters Guild of America and the Songwriters Guild Foundation, to create Music Creators North America (MCNA) and launch the “Fair Trade Music” initiative.

SPACQ, due to travel issues, was not available to sign the founding charter but did sign on soon after we returned from Washington. Since June, the Society of Composers and Lyricists (SCL, based in Hollywood and with a New York chapter) has officially signed on to the MCNA charter as well.

Also in Washington we announced that a further network of alliances between the MCNA, the European Composer and Songwriter Alliance (ECSA), the International Council of Creators of Music (CIAM), the Pan African Composers and Songwriters Alliance (PACSA) and the Alliance of Latin American Creators of Music (ALCAM) had been formed.

We now have a truly global network of pure music creators’ organizations in place. We have signed many documents and letters in support of issues including the need to keep the global collective rights management system transparent, streamlined and strong. All alliance members have endorsed the Fair Trade Music Principles and initiative.

The Fair Trade Music initiative is designed to give all music creators a  voice and a fair position within our own value chain. We again find these words “fair” and “value.”

voice and a fair position within our own value chain. We again find these words “fair” and “value.”

The Fair Trade Music Principles read as follows:

1. FAIR COMPENSATION – Music business models must be built on principles of fair and sustainable compensation for music creators.

2. TRANSPARENCY – International standards must be developed and adopted, that ensure efficient and transparent management of rights and revenues derived from the use of our works. These standards must apply to all entities that license such rights, and which collect and/or distribute such revenues.

3. RECAPTURE OF OUR RIGHTS – Music creators must have the ability to recapture the rights to their works in a time frame no greater than 35 years, as is currently available to songwriters, composers and artists in the United States. The effect of recapture of rights must apply globally.

4. INDEPENDENT MUSIC CREATOR ORGANIZATIONS – Music creators must have their own independent entities that advocate for, (and) educate and provide knowledgeable support for members of their community, including aspiring songwriters, composers and artists. Music creators speak for themselves, not through those with interests in conflict with them.

5. FREEDOM OF SPEECH – Music creators must be free to speak, write and communicate without fear of censorship, retaliation or repression in a manner consistent with basic human rights and constitutional principles.

I’m very proud that the SCGC is now a respected, trusted and integral voice within the MCNA and these broader alliances.

Fairness and value. These are the words that continue to leap off the page for me.

Make no mistake, I understand that these words are not economic concepts — but they give our lives meaning. I do hope these principles can be shared and honoured, as we try to attain our goal of improving screen composers’ and all music creators’ ability to achieve and maintain fair and sustainable compensation and working conditions.

It is our desire to show leadership by example and our hope to find that these values are still vital in Canada and beyond.

Marvin Dolgay is the President of the

Screen Composers’ Guild of Canada

![]()

The Value of SCGC Membership

by John Welsman

The SCGC is embarking on a new initiative to increase membership by bring emerging and veteran screen composers into the fold. Let me share some of the many benefits of joining the Guild, as well as what the Guild has meant to me over the years.

For members who are early in their career curve, we offer the Apprentice Mentorship Program, where the Guild matches emerging composer apprentices with more experienced composer mentors, allowing them to work with them in their studios for a period of time in any and all capacities. They may even receive a modest stipend for their services. Many “graduates” of the AMP have stated that the experience was a game changer for them.

The SCGC organizes a large variety of seminars and offers members many opportunities for professional development, as well as giving them access to many hours of online instructional video and tutorials. We’ve held engineering workshops, orchestral reading and master classes, workshops in negotiating and game music seminars to name just a few. Members (and many producers, too) find the SCGC Model Agreement helpful when looking for a boilerplate agreement that covers all the basic contractual needs, in many cases of both composer and producer.

One of the greatest benefits to members is undoubtedly the SCGC discussion list, where members ask questions ranging anywhere from tech and troubleshooting to business and negotiation pointers. With access to this incredible brain trust, members are getting hundreds if not thousands of dollars worth of advice for which they otherwise would have to pay a lawyer or some other professional.

That generosity is what’s so wonderful about our Guild; while we’re all competing for the same jobs, we all know that there’s way more to be gained by sharing information and helping each other than by keeping cards close to our chest and perhaps letting another bad, and potentially precedent setting, composer agreement get signed.

On a more personal note, what I’ve enjoyed most over the years is the sense of belonging to a community. Most of us work alone in our darkened studios day in and day out, but I find that to gather once in a while and trade war stories, discuss problematic trends, and exchange ideas for solutions is the best thing about our organisation. If you’re not a member, you’re outside all of that, and missing all the advantages of an incredible support network.

Additionally, and importantly, the SCGC is the composer’s strongest advocate out there in the world, connecting with other organisations and enabling us to find common positions on how best to lobby and advocate for the livelihoods and rights of screen composers in Canada. The marketplace is changing fundamentally, with downward pressure on music budgets, and the entire model for compensation for our creators’ rights faces a seismic shift as viewers’ eyes turn increasingly away from television to the internet, where the downstream performing rights revenue seems to be a small fraction of that for television. It is urgently vital to be a part of communities that give composers a voice in that marketplace and with policy makers. SCGC members believe that there’s power in numbers, and when we’re advocating to industry and government, we want to be talking as one voice that truly represents all media composers working in English in Canada. At this point, with around three hundred members, we represent the majority of those screen composers. But in fact, not all of them. A stronger member base would help us carry out this work more effectively.

Some of you might have heard of us but are hesitantly sitting on the sidelines. Joining may be one of those things you just haven’t gotten around to doing. Others have joined and perhaps fallen away, content to leave the heavy lifting to others. I know a few veterans who just aren’t joiners. If you’re working in music for motion picture or other media, you need to be a part of this. If you care about having a viable career in music for media in the future, I suggest that now is the time to step up to the plate and be counted. I strongly encourage you to join.

![]()

********************

Inside the Canadian Film Centre’s Slaight Music Residency

Inside the Canadian Film Centre’s Slaight Music Residency

by Jeff Morrow

I’ve just spent an hour on the phone with Yuri Sazonoff going over my orchestration; a piece that I’ve written will be recorded at Revolution Recording in a few days with a fifty-piece orchestra. This is one of many incredible — and indelible — experiences I’ve had in the last year as part of the Canadian Film Centre’s Slaight Music Residency.

By now, I’ve had some practice talking about the experience. Many of the industry veterans and mentors who’ve been a part of the program started by asking, “What is this CFC thing anyways?” For lack of a better explanation, I’ve described it as a bit like a film-scoring MBA. You enter the program with some experience and a fledgling career. You leave with a wealth of amazing anecdotes and wisdom, a revamped demo reel with a year’s worth of interesting and challenging work, and many new friends and contacts in the film industry.

My fellow residents and I had workshops with Christophe Beck and Howard Shore. We flew to L.A. to meet Mark Mothersbaugh, Sean Callery and Charles Bernstein. We worked through an entire scoring process with a CFC director and Mychael Danna. From spotting to presentation and revisions, Mychael facilitated the process. He would pepper our conversations with statements like: “Well, when working on Pi …” or “Atom and I work together like this …”

It was a privilege to work on two of the CFC’s short dramatic films. These were expertly crafted by CFC directors, producers, writers and editors, and, thanks to the Slaight Family Canadian Music Fund, I was given a reasonable music production budget. For each film, I was able to record a small group of Toronto’s best musicians, including George Koller, Mark Kelso, Davide Direnzo, Steve Lucas, John Johnson and a fantastic string quartet led by Lynn Kuo.

I shared this experience with the other music residents, Allie Hughes, Chris Bartos and Todor Kobakov. It was a thrill to work and learn with such talented people; the music they created throughout the program set a very high bar. At one point, we were tasked with scoring an episode of Flashpoint, to be critiqued by Amin Bhatia and Ari Posner. Todor and I also scored an episode of Murdoch Mysteries concurrently with Rob Carli. These exercises allowed us to gain insight into these composers’ practices, and it was always fascinating to see how different composers approached the same scene.

The whole year was an overdose of inspiration. The opportunity to discuss film and music with so many talented people has encouraged me to reflect on my own process and has ultimately made me a better composer. When you hear from, talk to, and work with brilliant composers and filmmakers, you can’t help but want to get back to the studio to write more music.

I am forever grateful to the CFC for creating this program and the Slaight Family Foundation for sponsoring it and for giving me the chance to participate in its inaugural year. Though they are not musicians themselves, Kathryn Emslie, Larissa Giroux and Sheena MacDonald have put so much work into the residency. They curated a rich and diverse set of people and experiences. And I thank all of the SCGC members who consulted, gave workshops, Skyped in, and developed this program — there are too many of you to list here. You have been a huge part of getting this program off the ground. I can safely say the Slaight Music Residency will make a huge contribution to film music in Canada and our community in the years ahead.

![]()

Toronto Ravel: Just for the Love of It

Interview with John Herberman by Erica Procunier

The short version:

Who: Anyone and everyone who is interested in a deeper understanding of orchestral music

What: An orchestration study with special guest lecturers and socializing

When: The third Thursday of each month (except July/Aug/Dec)

9:30 a.m. @ C’est What? on Front St.

How: $20 at the door for lunch

Why: Just for the love of it!

Website: torontoravel.com

I sat down to chat with John Herberman about opening the Toronto chapter of the successful Ravel study group. The Ravel study began in Los Angeles and has since inspired similar groups in New York, Chicago, Seattle, San Diego, and Tokyo.

Erica Procunier: What is Toronto Ravel?

John Herberman: Toronto Ravel is a study group affiliated with a similar group that’s been going on in Los Angeles for five years. Ron Jones, the composer for Family Guy, started the L.A. group in 2008. Ron Jones is a confirmed orchestral guy who writes with a pencil and he also believes that sharing and collaborating is way better than hoarding and isolating yourself. He believes in giving things away — giving knowledge away, giving experience away. That’s how L.A. Ravel started. It was a study group to get together to go through Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé.

Erica: Why Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé?

John: It is that specific piece because, for a film composer, it’s an encyclopedia of everything that anyone would want to know about orchestration. It’s got everything in it. It’s not like learning from a textbook. There is so much to learn from it, and each bar has something new to offer. It’s generally regarded as Ravel’s masterpiece.

Erica: So, why is this going to be more than just a study group?

John: It’s not just a study group because there’s another underlying goal. The goal is to get people in a room who wouldn’t normally be in a room together and don’t normally get a chance to talk to each other. In [Ron Jones’s] vision, that might be an eighteen-year-old budding composer in his jeans and baseball cap sitting beside John Williams in his jeans and baseball cap. They are there to study Ravel, but they are also sitting beside each other and who the hell knows what’s going to happen. It’s also to foster a situation where, for example, a composer is doing a demo and she starts programming a flute part and says, “Wait a minute, I sit right beside the first flute in the L.A. Phil, why don’t I call him and he can come and play the demo for me?” And people start to get together and form these little collaborations, and maybe some people will stop doing it alone in their cubby and maybe some people will start being a little more open. We are taught to be hoarders as freelancers and it’s not the best way to work. At least that’s where I’ve come to in my life. It’s people who, from whatever walk of musical life, love orchestral music and want to learn about it. It’s a chance to come together (as my logo says), just for the love of it. It’s a chance to spend an hour studying orchestral music with no ulterior motive. There’s a meal shared afterward, which is the best way to be social.

Erica: How is Toronto Ravel going to be different from L.A. Ravel?

Erica: How is Toronto Ravel going to be different from L.A. Ravel?

John: L.A. Ravel was primarily for musicians and composers. We are going for a much wider audience here. If you notice on the press release, we have so many different partners: The Directors Guild of Canada, SOCAN, The Canadian Music Centre, The Toronto Musician’s Association, The Screen Composers Guild of Canada, The Canadian Cinema Editors, The Canadian Film Centre, and The Academy of Scoring Arts. All of them are throwing their support behind this and publicizing it to their membership. So I’m hoping we’re going to have a much wider audience for this.

Erica: How are you going to make the program in-depth enough for composers, but still wide enough for non-musicians?

John: I don’t know the answer to that yet, but that’s going to be my challenge. As I think about it, I don’t think it’s going to be as hard as all that. The reason is because a lot of our membership, (and I think this is different from in L.A.), a lot of our membership is not highly-schooled and that is by no means a criticism. I think that’s the reality. So if I got highly technical, I think I would leave a lot of our SCGC members behind. Oh the other hand, the screen composers are going to want to get some useful stuff out of it. But they’re going to have a score right in front of them and they’re going to be making notes on the score. And then they can go figure it out by themselves. I think for the non-musicians, the directors or editors for example, (I think editors are closet musicians anyway), they might have their heads blown off by some detail, but I think they’re going to be amazed at what goes into creating a piece like Daphnis and Chloé. And even if they don’t understand every technical thing I say, it will be different for them from that point on. They’ll see it, hear it, and maybe view orchestral music differently from that moment.

Erica: Can you tell me a bit about your plan for the guest speakers?

John: Initially, I get to be the teacher guy. I’m hoping that over time I become more of an occasional teacher and a moderator and other people will take over the teaching duties. Ron Jones has agreed to be our first guest presenter via SKYPE. Because of the unique situation here in Toronto, I want to have people from all different walks of life become presenters. For example someone like Christos Hatzis from U of T, who is a phenomenal composer and has done some music for media and incorporates all kinds of media into his writing. I want to get conductors. I want to get filmmakers. I’d love to get directors to come in and talk about music in film and their approach. I aim to give this program a very wide appeal. It can’t be just music people, because then it will become just for film composers.

Erica: What is the commitment level like? Do you expect people to come to every session?

John: There is zero commitment. You come when you like. You drop in when you like. If you like the guest, come. If you can’t come, it’s not a problem. People have lives … people are busy. Missing one doesn’t mean that you will be behind on the next. Each meeting is self-contained in the sense that: “These are the bars we are going to be looking at this week, and that’s what we’re studying.” So, there is no commitment to come regularly. I’m hoping, of course, that everybody wants to come regularly. I want this to be huge.

Erica: What have they been studying in L.A. since they finished D & C?

John: In L.A., after they finished Ravel, they went onto Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and now they are starting John Williams’s Star Wars Suite in October (which I will be there for!)

Erica: Do you need to bring anything?

John: You don’t need to bring a thing. It’s recommended to have a copy of the score for following and making notes. Scores are available to be purchased online very inexpensively. There may be some extra copies to lend out at the meeting. One of the things that Ron Jones has provided is the entire Daphnis and Chloé Suites 1 and 2 sequenced into Digital Performer with audio rendered and lined up perfectly with a recording of the works. Ron sent it to me on a USB drive with one caveat — you can’t keep it to yourself. You have to run the group and give it away. That really sums up the sharing philosophy of all of this. We will be using that tool at the meeting and it will all be available to anyone who wants it. A pencil and eraser are also suggested if you’d like to take notes.

Erica: What is the schedule?

John: We will meet on the third Thursday of the month with the exception of December, July and August (I want to take the summer off). We meet at a very cool place, C’est What? on Front Street in their room with the stage. We will have coffee at nine thirty in the morning, and ten a.m. is the study. At eleven a.m. we will have a guest each time, and at noon lunch is served. The cost is $20 at the door, the majority of which will pay for the food provided by the restaurant, and $1 will be held to pay for the annual cost of our web hosting.

Erica: What effect do you hope to have on the Toronto arts and media community?

John: I hope that it becomes an important part of music for media in this city. I hope it becomes a focal point for new collaborations and new relationships. I hope that the people that need to in our world, like directors, gain a different appreciation for the ability of orchestral music to add a third dimension to what is essentially a two-dimensional medium. I want directors to understand why, if they ask a composer, “Can you do this?” that the composer may say, “No, I cannot, unless you have real people, real musicians on the session.” It cannot be done properly without. I believe that it doesn’t matter if it’s a nose flute or an orchestra. It’s better if there is someone sitting there blowing it, bowing it, hitting it, than when it’s a machine. It doesn’t matter how good the samples are. It’s a bit of a mission of mine.

Erica: How would you convince someone to come if they were unsure about it?

John: It’s really important that people understand that they don’t require previous knowledge. They don’t have to have prior study. They don’t have to understand theory. They don’t even have to have anything to do with orchestral music to get a huge amount out of Ravel. Yes, they will learn about orchestral music, but in a way that is really going to help them in their lives. It will open their ears, open their eyes, and improve the work that they do. Plus, it is going to introduce them to people that they simply would not get to meet. This is not to say that this is a networking opportunity, because I think it falls apart if people think they are being sold. But it’s a relationship building opportunity between groups that really just don’t get to do that. Plus you just get to hang out for two or three hours doing something just for the love of it. Have a bit of food, sit around with friends and then go back to work. What better way could you spend a Thursday morning? I would just encourage everyone to just come and see!

Erica: Are there many people helping you out?

John: This is way too much for one person to do. I’ve had some great help from some guild colleagues. Adrian Ellis has been fantastic getting the website up and running and doing the technical stuff. Janal Bechthold is going to be looking after social media. Nick Dyer has been invaluable as my right-hand man willing to take on anything. He is the point person for the venue and making reservations. There will be more people helping as time goes on because it will be way too much for one person. And besides, it’s counter to the philosophy if one person’s doing the whole thing because then it becomes about me, and it’s not. I’m no Ron Jones!

I would like to say a huge thank-you to Marvin Dolgay and Maria Topalovich for getting 150% behind this from the start. Even though this is an independent initiative, the support of the SCGC was crucial for it to be successful.

Erica: Now that we’ve got everyone on board, what’s next?

John: Tell your friends. All are welcome, tell your friends. Word of mouth is very important here. Everybody is invited. If someone off the street is interested, they are totally welcome. My goal is to have so much interest that we will have to find a bigger place to hold it at! I haven’t been more excited about a project in fifteen years. Please help spread the word. The first meeting is completely sold out. I hope it’s always like that.

![]()

********************

The Invisible Screen Composer:

Redefining Ourselves in the Digital Marketplace

by Adrian Ellis

In July, a link to an article was posted to the SCGC discuss list that first appeared on DigitalMusicNews.com in November 2012. It was titled “My Song Was Played 3.1 Million Times on Pandora. My Check Was $39…” and was a reprinting of a comment made on the site by Grammy nominated hit-song writer Ellen Shipley. In it, she laments the plight of songwriters, whose meagre earnings from the streaming service Pandora are facing further cuts of up to 85%.

Wow. Does that sound familiar at all? Although this article is focused on songwriters, the issues are at heart about creators’ rights and fair compensation, which are very relevant to us as screen composers.

The music and film industries both face many challenges. Changes in technology and the way in which people consume content have ushered in disruptive business models (such as streaming) that threaten the foundations of what many have come to rely on to earn a reasonable living. Individuals, businesses, and organizations have had to scramble to make sense of, and adjust to, these new realities, while governments attempt to navigate the increasingly complex world of copyright laws and reforms, amidst lobby pressure from often opposing forces.

These are all things we are thinking about all the time — or, at least, they should preoccupy us. We are working in a volatile and ever-changing environment and live in a state of anxiety about the future of our industry and livelihood. As if that wasn’t enough, I was horrified even further when I began to read through the comments posted regarding Shipley’s sentiments. Brace yourselves — here is a sampling of the more negative ones:

Boo hoo … She’s been making money on the song for the last 20 – 30 years. The idea that she still gets paid is what is insane. I have no sympathy for anyone who complains they are not getting paid enough for something they did in the 80’s. Copyrights should expire after 20 years as patents do.

… the songwriter conspicuously [sic] gives NO data as to what she would be paid if 3.1 million RADIO LISTENERS heard the song. … Wonder how much the computer programmer got paid per stream?

That’s ridiculous. When you see a person performing on the streets are you obiligated [sic] to pay them? After all, you have heard/seen/experienced their art have you not? When a songwriter puts his/her art in the digital domain, it is no different than [sic] performing on the streets. The digital world has created a place where music is passed around for free. This is no secret and it is not new. … If you want your music to not be free, then perform it live and charge admission.

If we’re going to piss and moan about stupid sh*t, let’s at least make it equal across all mediums and not just about the bleeding heart “artists” that were too busy doing drugs and playing guitar in their hayday [sic] than to do something to further humanity.

While counter arguments are presented, I feel as if I come across this stuff more and more on forums and in debates surrounding creators’ rights. It makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Where did this anti-creator sentiment come from, and how did it get so bad?

As I started meditating on the possible reasons, I began to see a correlation between what’s been happening in our industry, and the world at large; after all, we don’t operate in a vacuum. In the wake of the 2008 financial collapse, we are seeing people struggle to make a living while the gap between rich and poor gets ever wider. Amidst recessions, layoffs, bankruptcy, and foreclosure, perhaps the average working person would view with some resentment what we treasure so greatly – our creators’ rights, including performance royalties. Do they find it difficult to comprehend the idea of intellectual property, where a work can be exploited and bring in profit beyond the first measure of labour that was put in to create it?

I’m reminded of the tone of anti-union sentiments — the idea that unions create a system where lazy whiners can thrive and prosper. Having worked in that environment prior to moving to composing full-time (both as a member and as shop steward who sat on bargaining committees), I see both sides of the argument. There were times when some of my union brothers and sisters drove me to distraction with their self-entitled attitudes that expected the world while doing as little as possible. However, these were the inevitable “bad apples” that crop up in any situation, and I cannot see the logic in undoing years of positive action and workers’ rights, which were so hard-fought for. Sure, it’s not a perfect system, but does it really make sense to say, “Your deal is too good. Let’s do away with it,” instead of saying, “Hey — how about we get a good deal too?”

I could see how this connected to the misinformed opposing voices which surfaced during the Occupy movement. Detractors would post photographs of themselves holding posters proclaiming they were not the 99%. Some wrote about holding down three minimum wage jobs in order to make ends meet, and their pride in being masters of their own destiny, as per the American dream. Their feeling seemed to be that those subscribing to the Occupy movement were lazy, self-entitled, and looking for a hand-out. It was a head-scratcher; how had they missed the point of the movement, which was in part a reaction to the widening income gap, and the fact that most of the wealth is controlled by a fraction of the population, amidst bailouts saving the very corporations that put the country into an economic tailspin with their irresponsibility and greed.

There seems to be a similar and parallel gap growing in the business of being a screen composer. You are either working in the trenches for ever-shrinking budgets (and ballooning demands), or at the top making extraordinary sums for your creative work. Personally, the anti-creator comments really sting, because I for one am not exactly swilling Cristal while driving my Lamborghini down the strip after a decadent lobster dinner, wearing my Chanel sunglasses to prevent the reflections from my bling blinding me permanently. I believe that our creative product adds considerable value to any project, and when you look at the demands placed on us to compose, orchestrate, produce, record, and mix (the list goes on) broadcast quality work, and the years invested to master those skills, most of us make a very modest income.

There seems to be a similar and parallel gap growing in the business of being a screen composer. You are either working in the trenches for ever-shrinking budgets (and ballooning demands), or at the top making extraordinary sums for your creative work. Personally, the anti-creator comments really sting, because I for one am not exactly swilling Cristal while driving my Lamborghini down the strip after a decadent lobster dinner, wearing my Chanel sunglasses to prevent the reflections from my bling blinding me permanently. I believe that our creative product adds considerable value to any project, and when you look at the demands placed on us to compose, orchestrate, produce, record, and mix (the list goes on) broadcast quality work, and the years invested to master those skills, most of us make a very modest income.

The reality is that it is getting harder to make a reasonable living in this business — for everyone. In conversations with my filmmaker colleagues, I see that this extinction of the creative middle class has affected them as well — one is either making studio-level blockbusters, or pulling together a couple of hundred thousand for a scrappy, high-concept indie. We are facing many related challenges, including direct licensing, and the rise of streaming services such as Netflix and YouTube. Meanwhile, a lot of money is being made — by someone else.

Take one example: despite the woes that have plagued the industry such as the advent of advanced home theatres and piracy, the annual revenue from movie ticket sales in the United States was $10.83 billion US in 2012 , reflecting a steady upward trend since 1995 from $5.29 billion US. Netflix’s revenue was $3.61 billion in 2012, when Google expressed interest in buying the company for a reported $17.9 billion. With all this money being made from content to whose value we have contributed, are we getting a fair deal? The Pandora issue suggests we aren’t, and PROs are still wrestling to deal with traditional models of broadcasting moving inexorably to the digital realm.

Despite all this, we seem to lack the public sympathy. Perhaps the long-promoted ideal of the rich musician (the aforementioned Mr. Blinded-By-Bling) is coming back to haunt us as screen composers as well. As hard as it is to believe, we might be getting lumped in with a kind of moneyed elite, to be regarded with suspicion and resentment.

Is the true face of the screen composer absent? Are there huge holes in the public’s understanding of creators’ rights, their critical role in our survival, and our challenges in the digital marketplace? If so, how do we change this?

We tend to be a fairly shy, soft-spoken lot who feel more comfortable in a cave-like studio by the monitor’s gentle glow than in the public, stating our worth. We’re typically not joiners, and we like our boat most definitely not to be rocked. In our present circumstance, however, I believe we must come out of our shells. We have to address this problem of perception: we need to re-humanize and properly contextualize the music creator, and educate the public and our screen-content-creating brethren about our challenges and our value. It’s important to bring the public onside because public opinion helps drive change and shape legislation. We need to bring our creative partners onside because strong relationships will ensure that they’ll understand our position and even join forces with us.

More importantly, we have to do this in our voice. On an organizational level, the SCGC is a part of a number of initiatives that are working towards this through advocacy and education. One of these is Music Creators North America (MCNA), which was created in part as a response to the fact that most of the advocacy done on behalf of the music industry was via publishers, labels, and broadcasters, not the creators themselves. With the idea that the creator needs to have a voice in the conversation, MCNA has put forth a set of principles that make up the Fair Trade Music Initiative, including the requirement that music business models be based on fair compensation and transparency. The MCNA advocates for music creators in order to shape the dialogue around creators’ rights. Closer to home, our new alliance with the Directors Guild of Canada presents an opportunity for us to forge deeper connections with screen content creators in the film and television industries, and add our voice to the call for fair and sustainable working conditions. They, like us, are feeling the pressures of a changing industry, and I can see that we may have many shared goals.

As individual working screen composers, we have a responsibility to be informed and to participate in dialogues that will shape how we, and what we bring to the table, are perceived, even if that’s simply in the day-to-day communicating and networking that we do. I hope that many of you will feel compelled to participate even more actively, and I also hope to see more working screen composers who are not yet part of the SCGC joining up. I think the reasons to do so are clear and present, and together, we are stronger.

The issues we face are many and complex, but I am convinced this work is vital, not just to our surviving but to our thriving in the new digital marketplace. While the landscape may look bleak, I have hope that we will affect positive change if we reach out, speak to our value in our own voice, forge alliances within and outside of our community, and together work towards a sustainable future for our industry as a whole.

![]()

********************

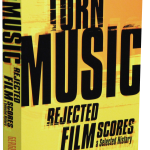

Torn Music: An Unexpectedly Entertaining Elegy for Lost Film Scores

Torn Music: An Unexpectedly Entertaining Elegy for Lost Film Scores

An interview with Gergely Hubai

by Chris Pauley

As screen composers, here’s a scenario we’re all too familiar with: you’ve poured your heart, soul and every ounce of your creative talent and energy into a cue only to have it discarded, edited past the point of recognisability, or replaced with a song or, shockingly, someone else’s music. Some of us, though, know that pain even more keenly, and have had entire scores replaced or otherwise butchered. When that happens, it may offer some comfort to know that it’s not so rare an event and that you are in good company, including a surprising array of cinematic greats, from Alex North (2001: A Space Odyssey) and Jerry Goldsmith (Legend) up to more contemporary composers like Michael Nyman (Practical Magic) and the industrial band Coil (Hellraiser).

No one knows these tales of disappointment and triumph better than Gergely Hubai, who has been a lecturer in film music history at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, and has been chronicling such tales for years. He has also demonstrated scholarship in such varied areas as the music of James Bond films and the rejected film scores of composers outside the Hollywood system such as Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg. He has also written on film music for various periodicals, including Film Score Monthly, as well as liner notes for a number of film score recordings, including rejected scores by John Corigliano (Music from the Edge) and Phillip Lambro (Los Angeles, 1937). Most recently, he compiled a history of rejected/replaced/butchered film scores into a book, Torn Music: Rejected Film Scores, A Select History (Los Angeles: Silman-James Press), and he was gracious enough to spend some time with Spotting Notes to tell us about it.

Pauley: Hi, Gergely! We had a great chat back in 2010 about the role of the internet in film music, and talked at length about you, your blog, and how composers might use the internet to get their music heard. Perhaps you can shed some light on your background and how that fits in with how you came to write this book.

Hubai: When we last talked, I believe I already had the manuscript for Torn Music finished. Editing and typesetting the book took about one and a half, maybe two years — it was certainly a lot slower than I’ve gotten used to during the release of film music recordings! In terms of your question, though, I’d say the exact opposite happened. It wasn’t so much that my work brought me to the book, but that my work on the book brought me together with lots of interesting people. Everything else that I’ve been up to, like providing liner notes for CDs, getting involved in soundtrack marketing and orchestra contracting, came out of my experience with Torn Music rather than the other way around.

Pauley: Tell us about the genesis of Torn Music. What compelled you to want to relay these stories of rejected and replaced film scores?

Hubai: What compelled me to write the book was the sheer number of urban legends and tall tales that surround the subject. “Allegedly” is a word that often comes up during the discussion of rejected scores. I simply wanted to eradicate this word and bring out the real details about these cases whenever possible. I also wanted to point out that there’s nothing shameful about having a score thrown out. I feel that while composers know about some of the key cases, they simply don’t know just how many cases there are, and how frequently it happens to even the biggest names. For them, I hope it serves a therapeutic purpose as well.

Pauley: You’re absolutely right. The sheer volume of stories you relay in this book is really oddly comforting, encouraging, and disheartening, all at once! It also makes you wonder what many of these scores actually sounded like. Other stories in the book, though, are far less familiar, either because the films are somewhat obscure, or because the stories aren’t as well-known. What stories particularly surprised you?

Hubai: Ninety-five percent of the time the stories in Torn Music can be summarized very simply: somebody (the director, the producer, the studio) didn’t like the score and they changed it. My writing was only about presenting these stories in an interesting way, but it usually boiled down to this simple notion. The remaining 5% of stories, though, were insane! For instance, awkward situations where a big composer is under contract to a label and it turns out in mid-stream (or even later) that the movie he’s working on had promised the soundtrack release to a different entity, then he has to bow out. That’s weird and fascinating at the same time. Another interesting thing is how often single instruments are credited with rejection. The most notable of those was Elmer Bernstein’s love for the ondes Martenot; that sound doomed some of the latter scores he worked on.

Pauley: You must have used many different sources in the discovery of these stories! Here’s a three-parter: how complicated a process was it to pull together the disparate elements needed to properly tell these stories, how often were you able to get stories directly from the artists themselves, and how long did it take to pull everything together?

Hubai: To start answering from the end, getting everything together was a gradual process that I can’t really count in years. You just take a note of what you read where, put together the puzzle pieces and wait until everything in your head clicks to form a narrative. As to talking with the artists themselves, I’d say that I found it easier to talk with people who were already semi-retired or had nothing to lose, so to speak. That, by the way, went both for composers and directors! Frankly, the hardest part was deciding what to keep and what to cut. I originally intended to cover everything, but when that turned out to be impossible, for a number of reasons, I had to make some cuts that were quite hard.

Pauley: Maybe we can hope for a sequel, then!

Hubai: (laughs) One never knows; I’d love to see an expanded or updated version come out sometime in the future, but that’s up to the publisher! Maybe even an online database of some sort.

Pauley: We’ll keep our fingers crossed. The altering

or removing of a score happens to composers all the time, yet it has to sting. I imagine 95% of our readership have their own stories of this kind of thing happening! Did you get any kind of push-back or resistance from producers/directors/composers while you were collecting stories? How did you handle it?

Hubai: During the writing of the book, I e-mailed, called, and mailed many, many composers and directors — or when there was no other alternative, their representation. I’d say about one out of every five attempts resulted in some form of success, which is not that surprising when you consider the nature of the project. After all, you’re approaching strangers to tell you about their most painful memories with no possible benefit apart from a little therapy session. That said, most of the replies I did receive were supportive and informative, with the exception of one composer, who wrote me a letter condemning the whole book and telling me very general things about the business that I already knew. He gave me the permission to print his letter, but I naturally had no interest in this. Apart from that, I didn’t have any sort of pushback from the involved parties who took the time to get back to me.

Pauley: What’s your favourite story from Torn Music?

Hubai: Returning to weird instruments, my favourite may be Paul Glass and his unused score for an episode of Columbo (“The Greenhouse Jungle” from Season 2). I like this story very much because I had very little to begin with (a casual mention in an archival interview) and through some detective work, I tracked Paul down in his Swiss retreat. We had multiple talks, which not only gave me enough clues to identify the specific episode, but also uncovered that it was once again because of one instrument, the heckelphone, a weird oboe-like instrument, that a higher-up didn’t like. I talked a lot with Paul after this and I even visited him when he recorded his latest film score in Cologne.

Pauley: So what’s the response been to the book, Gergely? What kind of audiences (outside of obvious ones, like SCGC members) have embraced the book?

Hubai: I’m happy to say that it’s mostly positive. I didn’t find any outright negative reviews online, just some that were more critical about certain aspects of the book — which I can appreciate. For example, some may feel that a random television movie doesn’t deserve the same length of discussion I’ve given to The Exorcist or Torn Curtain. Perhaps my favourite response was on a film music message board, where one of the members proudly announced that Torn Music was the only book on the subject he owned. That was touching because it came from my precise target audience.

Pauley: I can relate to that. It’s also, because of the way it’s organized into individual vignettes, a nice casual read. Dare I say, it makes a nice bathroom book (provided you have a lot of film music aficionados visiting your bathroom). So what’s next for you? Any new projects/follow-ups to this in the offing?

Hubai: I have a lot on my agenda (perhaps a bit too much) and I don’t know what comes next. For instance, I have a completed manuscript about the film scores of Miklós Rózsa in Hungarian, and I’m looking for a publisher for it in his native country. Other things going on are projects I shouldn’t talk about because I’m afraid someone may finish one of my ideas faster than me! (He laughs.) For now, providing liner notes for CDs is a great way to pass time between bigger projects because they get published so much quicker.

Pauley: Multiple plates spinning is the way we keep engaged! Keep at it, and we look forward to seeing whatever it is you come up with next. Thanks for your time!

Hubai: My pleasure! Glad to hear the book is getting attention in Canada!

![]()

*********************

Mychael Danna: A Year to Remember

Mychael Danna: A Year to Remember

An interview by Erica Procunier

Mychael Danna has had quite a year, winning the Oscar for his work on Life of Pi, and most recently an Emmy for his work on World Without End. Originally from Burlington, Ontario, he studied composition at the University of Toronto and became the composer in residence at the McLaughlin Planetarium from 1987–1992. Since his debut feature film in 1987, Atom Egoyan’s Family Viewing, Mychael has written more than seventy scores for feature films and television. He has worked with many acclaimed directors such as Bennett Miller, Terry Gilliam, Marc Webb, Valerie Faris, Deepa Mehta, Mira Nair, Joel Schumacher, Denzel Washington, Atom Egoyan and Ang Lee. Mychael is also a Grammy and Emmy award nominee and the recipient of many Genie and Gemini awards. In 2013, Mychael won the Golden Globe and the Academy Award for his score to Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. He was also nominated, along with vocalist Bombay Jayashri, for Best Original Song for “Pi’s Lullaby” from Life of Pi. Mychael was kind enough to speak with Spotting Notes about his adventures at the Oscars, his career, and his outlook for the future.

Erica Procunier: Congratulations on your win at the Academy Awards! It’s very exciting to see one of our own members win one of Hollywood’s highest honours. It must be a very proud moment for you. Can you tell us about how you and Ang Lee are feeling?

Mychael Danna: For Ang and me, it really is a wonderful moment because this was a very difficult film to do. In all departments, we struggled mightily with the idea of taking this universally agreed upon “unfilmable” book and turning it into a motion picture. It was something we knew from the beginning was going to be difficult, but how difficult we didn’t know until we were deep into it. Certainly, there were many moments when we felt that all the people who said it was impossible were right, and that we had taken on something that was going to end in failure. We would all agree this was the most difficult thing that we’ve ever had to do.

We got to a point, (for Ang it was four years, for me it was almost exactly one year), where we finally had a screening and we were able to watch the film together. It was only two months before the release date and we had recorded the music and had most of the visual effects in. Up until they dimmed the lights that day, we were full of doubt and fear. When the lights came up, we sat in complete silence and no one said anything. There was a real feeling in that room that we had got to where we were trying to go. From that moment, Ang just started smiling and has not stopped smiling since. It took a tremendous weight off our shoulders.

Then it went out into the world, where it got a very warm reception from every country in the world. It’s a truly international film. (The film has now grossed over $600 million worldwide. – Ed.) I think we knew it that day. We knew that people would feel what we’ve done here. After a very difficult journey, it was very gratifying, and so to have awards on top of that feeling is wonderful, but honestly the smiles had begun before that. Win or lose, it really wouldn’t have taken that away from us. Of course, having the world embrace it, and having awards from our peers, people who understand intimately what it is that we do everyday and how difficult a film like this is to make, that’s fantastic.

Erica: Have you been able to take a bit of a break or holiday after the awards season push?

Mychael: No. No holidays. I haven’t stopped. I did Atom’s film, Devil’s Knot, right after I had finished Pi. Then, by the time Devil’s Knot was finished, awards season was in full swing. It’s been intense. Right after my agent saw the film, he said “Get ready for a ride!” and I didn’t really know what he was talking about. Now I do. It’s extraordinary and it’s fun much of the time, but it’s really intense and relentless. It’s as hard and as much work as making a movie. It’s fascinating. It’s a whole other art. It was a really intense experience that went up to and past the Oscars, because if you’re fortunate enough to win, then you do a lot of follow-up interviews and events. Those are literally still going on. This week I think I have two, then I will actually be finished with Life of Pi.

Erica: It’s generally not composers doing these big interviews. What was it like as a composer to get to talk so much about what you’re doing?

Mychael: It’s a wonderful opportunity to explain to people what it is that we do. Obviously, you can’t go into much detail. But it’s a great moment to be able to make what we do known to people who go to movies and don’t really think about or notice the music in a focused or educated way. It’s a great opportunity to make them notice. In a film like Life of Pi, where a lot of the dramatic power comes from the music, (just given the kind of film it is where there are big stretches with no dialogue), it’s a moment where people do notice the power of score.

Erica: Can you tell me a little bit about your early days of film scoring?

Mychael: I went to the University of Toronto for music, and composition specifically. There were very few film music departments anywhere, and Toronto did not have one. It was very much an old school music composition program. I also did some ethnomusicology and other areas of interest, early music and so on.

Erica: Did you choose to do that knowing you wanted to be a film composer?

Mychael: I knew I wanted to be a composer. I had no idea how or what that was going to lead to. I actually had very little interest in film music as I was growing up. I was exposed to film like everyone else, but it wasn’t something that I found very interesting or compelling. I’m definitely not one of those people who heard a score or a certain composer in a movie theatre, and went, “Oh, that’s what I want to do.” I wanted to be a composer since I was very young, but it was based on classical western repertoire and music that I heard my father singing (he was an amateur singer). I was very attracted to eighteenth and nineteenth century symphonic music. That’s what brought me into music and that’s what took me all the way into studying composition in college.

I grew up in suburbia, but once I came here to the University of Toronto, to the city, the rich multicultural explosion that was going on at the time was incredibly stimulating and inspiring to me. It was a whole new world opening up, of different instruments and different ways of looking at music. At the University of Toronto there was a decent ethnomusicology program and that was what really excited me. But again, I had no interest in film. What I was doing for fun was sound and music for theatre. I did a film score for a little educational film, from which I actually got fired. That was my very first film experience. I did session work for bands on synths. I was kind of trying all sorts of things. I got to know the planetarium composer in residence right next door at McLaughlin, which eventually ended up being my job. So it really was a wide experience of feeling my way into how I could possibly make a living writing music.

Theatre was the place that I had the most fun. And that seemed to be the best fit. I liked the collaborative spirit. I liked working with other people to a common goal. It was in that world that I met Atom Egoyan and we began working together on his first big feature. So it really was kind of a mistake. And as I said, my first film experience was very unappealing; working for somebody who was looking for something that I didn’t get. It was an interesting first experience, but Atom and I approached it more like theatre and it was in an art driven way. It was truly fun and stimulating. I was able to apply all the things that were interesting to me — non-western music, minimalism and electronics. Together, we learned how to make films and to score films.

Erica: Did you have anyone to guide you along the way?

Mychael: No. I never had a mentor. I mentor a lot of people now, but I did not have that experience. I had to figure out how to do everything myself. How to synchronize picture with sound, for instance. It was not easy back then. I figured out all of those things myself. I didn’t have any guidance. I was in a vacuum in that sense. There just wasn’t a film music community here in Toronto at that time. Certainly there were a few people doing it — Howard Shore was one of them — but not many were doing the kinds of films I was doing. We were all just in our own worlds and coming up with our own ways of doing things, using our own solutions. Perhaps that’s why when you look at a lot of the work and a lot of the people that came out of that time, it’s a lot of really interesting stuff. It’s because a lot of individuals had different approaches to the same problems.

Erica: You’ve recently aligned yourself with the Canadian Film Centre as Composer Chair for the Slaight Family Music Lab. Why is that relationship important to you?

Mychael: It’s always hard to come up in this kind of a career at any time for different reasons. I think now the challenges are very different. I don’t think it’s possible any longer to do it the way I did it. It takes networking and the ability to meet other people who are doing the same thing. You have to have a community like that. The CFC is really a fantastic place. I wish there had been a place at my time where I could have done workshops and understood how to do things. It’s important to me, having never had a mentor. It’s kind of fun to be involved in that sort of relationship at this point.

Erica: And it’s been going well?

Mychael: Yeah, it’s been wonderful. It’s been a particularly intense year for me with a lot of travel and I’ve been away a great deal, but the residents in the program are incredibly talented. It’s been great to do some fun things with them and introduce them to some work environments and people that I know in L.A. It’s good to just work through their most important working relationships, like with the director, in an actual working environment.

Erica: When did you decide that it was imperative to move to L.A., and what was your recent motivation to move back to Canada?

Mychael: I was very, very established when I went to L.A. I was already working on L.A. based films, New York based films, and all kinds of international films. It’s not like I went there to have a career. I had a career here, an international career. It just got to the point that there was a great deal of travel back and forth going on at that point. My wife and I were recently married and we were about to get a place together and we just thought, “Well, this will be fun. Let’s change everything up here and go to Los Angeles.” Really it was more of a lifestyle decision than a work decision. It certainly turned out to be incredibly fruitful for my career. But if you really look at it, how different would it have been? There are certainly a few films that wouldn’t have happened or might not have happened if I hadn’t have been there. But if you look at my biggest films, the most important ones that I’ve done in the last ten years, a lot of them are actually New York based. It didn’t make or break my career. L.A. is certainly a lot easier place to work from. The infrastructure is very developed there. It gave me a different perspective on a lot of things — just living in another country for a while. We moved there in 2004 and then we have two small kids, and we always felt that we wanted them to go to school here in Canada, so that’s why we came back. Our decision was based on non-career things. That being said, it helped me make some great relationships. It’s certainly a wonderful place to be a film composer, no question about that. I’m glad I didn’t go earlier — I already had my voice. I had a distinct style and I already had a stable of directors that I was working with and had relationships with. I was fully formed by the time I went down there. I think it would be a confusing place to go if you’re young. I actually think it would be harder to develop as an artist there.

Erica: What is your relationship like with your agency?

Mychael: I’ve had the same agent for twenty years. More than twenty years. So pretty good, pretty close. We worked together on my career. There’s a lot of strategic thinking. A lot of young composers ask me, “When should I get an agent?” I know that they think that agents get them work. That’s not actually how it works. Agents do not get you work, or only a small percentage. You get the work first and they negotiate the deal, that’s their strength. But you have to build your career by yourself. Certainly until you have a career, no one is going to be interested in representing you. It’s basically as simple as that.

Erica: Can you tell me a bit about your studio?

Mychael: My studio is incredibly basic and would probably shock most composers. I’m in Logic and I try to keep it all in the box. The main reason for that is that I travel a lot. I end up writing all over the place. On Life of Pi, a lot of it got written on a laptop. You can’t have a lot of peripherals and make it work. Depending on where Ang was, he wanted me there with him writing. So, my laptop was my rig. I had a little portable USB keyboard and a laptop. My studio is kind of jaw-droppingly simple and I’ll bet I have the most stripped down studio of anybody in the Guild. It depends on what you’re doing, and obviously every project’s different, but on Life of Pi I obviously didn’t record anything myself. I had my laptop and we’d hook it up with whatever Pro Tools rig happened to be in front of me.

Erica: I’m interested in the process you go through from start to completion. Who are the key people and positions that are really important in helping get your music delivered?

Mychael: Every project is different in every way. I feel like I almost don’t even have a base anymore. Every picture seems to happen in a different city. If we talk specifically about Life of Pi, it was written all over the world. Some of it was written here in Toronto, where I have a studio set up. A fair bit of it was written in New York, where Ang had an early post-production office. He needed to be reviewing shots every day, so I went there and worked off a laptop. We went to India and wrote the song there. Then we were in L.A. for the last four months, where there was a copy of the rig that I have here in Toronto. It wasn’t anything particularly ground breaking: it was Logic and Vienna on towers as opposed to laptops. That was easier to work on physically more than anything. For the last three months, there were three of us working — Rob Simonsen, Duncan Blikenstaff and myself. They helped with the many and frequent picture changes, conforming, arranging and all those sorts of things. We worked very intensely as a team on the Fox lot with Ang working only a hundred yards away and coming over a couple of times a day to hear things. We would have different cues on different rigs. We had three writing rigs and a slave machine with some sounds on it in this bungalow. Duncan had seven cues on his rig, Rob had ten, and I had twenty on mine. It just worked like that. It was manageable and everyone could stay up to date with picture changes. That’s how the last four months went and basically everything was written already by that point.

Near the end, the orchestrators got involved. My usual orchestrator, Nicholas Dodd, was not available. So I ended up using eight orchestrators, which was challenging in a lot of ways, but we made it work. It was definitely not desirable for me not to be with my usual orchestrator, but the stuff was coming in so late that we needed multiple people working on it. The one that I’d used before was Dan Parr, who is Toronto based. He’s incredibly talented and we work together very well. He was my one safe familiar orchestrator I knew I could depend on. But there was so much material that we had seven other guys, and they came through. Brad Haehnel is my long time engineer, who started at Manta here in Toronto. He was the head engineer in L.A. and ran the main sessions there. I had engineers all over the world. Another one in Toronto is Ron Searles, who is also ex-Manta, and we recorded the gamelan ensemble at CBC. It was a complicated multi-national effort and took a lot of people in a lot of places. We had several editors going at the same time. We had an editor whose only job was to cut orchestra and all the Indian instruments and percussion and bring them into proper grid. There were also several Pro Tools guys. Every team is different, and the team changes from film to film. The film I just finished with Atom had a very small team. It can go from one extreme to the other.

Erica: For those of us who have not yet had the pleasure of working with an orchestrator, how far do you take your own arrangement, and what do you hand off to them?

Mychael: It’s pretty detailed, and in a lot of cases it’s almost indistinguishable from the mock-up. Especially with a director like Ang or Atom who are very involved in the sketching stage. They’ve heard the midi sketches many times and they’re all kind of orchestrated already. For example, there’s flute, clarinet, strings and brass. You might be able to get away from that orchestration a little bit, but they’re going to be aware if suddenly the flute is doubled by bassoon or any extra things like that. Some of those things happen, but more often than not, my stuff is pretty much pre-orchestrated with the exception of strings and brass that are often just done in a general way. The strings are all on one track and not divided up and voiced out properly. Sometimes some voicing might be done, certainly solos, but that’s the lion’s share of the orchestration work — strings. If you heard the sketch and then the final mix, other than the obvious extraordinary sound quality and musicianship that is missing from the sketches, it’s very close. And so they just get a midi file, or depending on which of the eight orchestrators it was — Dan for instance — I could just send him a Logic file. All the time signatures are correct and everything’s sorted. A great deal of the work’s been done already.

Erica: So, it’s much different from the classical use of the word orchestration.

Mychael: Certainly there are places where we say, “Soup it up! Go for it.” But in a lot of these projects there’s a lot of detailed intimate writing. They’re not a big wash of nineteenth century orchestration. But, I have done films where the orchestrator certainly takes it to another level. But on Moneyball for example, and many of the other films that I’ve done, the directors want to be minimalist with the music.

Erica: You were also nominated this year in the Best Original Song category for your collaboration with Bombay Jayashri. Do you have any advice for composers who may be asked to collaborate with songwriters in the future?

Mychael: You find your strength and you bring in somebody who can supplement what you’re good at and maybe supplement the things that you’re not good at, or that you need to fill in on this particular film. Obviously, for a film where we wanted a Tamil language lullaby, Jayashri was supplying things that I would not be able to. I sketched the melody out, but I was very open to her making it her own and making it Indian. She did so and did it in a beautiful way. It’s fun to write with other people. I enjoy that. You just have to be open and collaborative and every situation is different. I didn’t feel it was any different from doing the score and collaborating with Ang, or collaborating with Devotchka on Little Miss Sunshine, or collaborating with the orchestra. A great deal of the shaping happens after it’s orchestrated and they play it through. Then you can take it to another level. I will change a lot of things and I will double things and get parts printed depending on how much time I have. You can take the orchestration to another level and shape the performance. It’s the same thing with the collaboration with Jayashri. We were hanging out together talking about what our goal was, what we were trying to accomplish, and then we just started to play.

Erica: Have you ever felt any pressure to follow trends in Hollywood, or can you ignore that and go on your own path?

Mychael: I think that’s one of the reasons I’m really grateful for my non-California upbringing. I grew up in Toronto in a time when independent film was really flourishing and I started in pure music and worked in theatre first. I came at film from a different angle. Growing up, I heard film music, but I didn’t find it particularly interesting and wasn’t all that curious as to how they did it. So when I started working with Atom, we really just came at it from a theatre music perspective: — what do we want to do and how can we get there? — as opposed to: how is it supposed to be done? I never listened to other film music until later in my career. So no, not really. I’m listening to a lot of different music all the time. But certainly I don’t feel pressure.

Erica: Are you listening to any other artists or composers to influence you, or just for enjoyment?

Mychael: Each project dictates what it is that I’m going to be listening to. And I will study very diligently, whatever it is I need to study — if it’s Indian music, or Armenian music, or medieval music. But what do I listen to? My favourite thing right now for some bizarre reason is … dance music. I like house, I like a lot of adrenalized dance music. I can’t explain it! That’s what is going on a lot of the time when I’m driving.

Erica: Are there any specific artists that come to mind?

Mychael: That’s an interesting question because I was noting that I don’t really listen to the same artist twice. If I have 200 tunes, there are probably 180 different artists. I listen to Pandora, where it asks, “Do you like this song or this song?” and then it just starts playing.

Erica: Oh, sort of like the app Songza, with its curated playlists based on your mood?

Mychael: Yes, I think I would like that app. We also have Satellite TV with a hundred music channels and I often have it on dance, and when I hear something I like, I’ll download it. It’s kind of bizarre, but then you know, a year ago I was really into old-time banjo. So I kind of go through moods like everyone does. In a month I might be right off this whole thing. In a way it’s easy and also hard to be introduced to new music today. It used to be that you listened to a radio station that had your style in mind, but those days seem to be gone. You can be specific,but it’s fragmented now. I love stuff like that where you can just discover and find a whole bunch of new things you’ve never heard before that you actually like. By the way, the last channel I would listen to would be the film music channel! I can’t imagine listening to that!

Erica: Well, it wouldn’t have the visuals with it …

Mychael: That’s a whole other discussion about whether film music deserves or has a place outside of film. It’s been coming up for me a lot lately because people have been asking for a Life of Pi suite that they can perform. I don’t feel that it should be taken out of the film.

Erica: You can pretty much have your pick of any project you want. So what’s next for you?

Mychael: Well, there’s nothing inked right now, but my next release is the Atom Egoyan film Queen of the Night. I’m really looking forward to getting back into work and moving forward. This has been an incredible moment in my life. It’s something that I’m still processing. In a lot of ways, it doesn’t feel real yet. But I think that’s probably a good thing. I don’t see it changing my attitude towards my work, and I don’t see it changing my career. I’m doing the exact kind of films with the exact people I want to work with. I don’t imagine that things will be all that different … but ask me again in a year!

![]()

********************

MEMBER NEWS

Compiled by Janal Bechthold

Appearances

CFC Slaight Music Residency:

Mychael Danna chairs the film composer stream of the Slaight Music Residency. Darren Fung is program coordinator, with the following composers appearing as panelists and industry experts: Lesley Barber, Amin Bhatia, Rob Carli, Marvin Dolgay, Todor Kobakov, Mark Korven, Craig McConnell, Neil Parfitt, Ari Posner, Donald Quan, Yuri Sazonoff, Marty Simon, Bill Skolnik, Jeff Toyne, and John Welsman.

ComicCon:

Robert Duncan was featured on the “Go Behind the Music” panel.

Atlantic Film Festival:

“From Screen to Score” performances and panel discussion featuring Asif Illyas and Chris Pauley, with other guests.

Toronto Animation Arts Festival International:

Neil Parfitt and Amin Bhatia are featured on a panel about composing music for animation.

Cineworks Independent Filmmakers Society:

“Pictures and Melodies: Working With a Composer” panel featuring Graeme Coleman, Michael Neilson, and Tim McCauley.

Billboard/Hollywood Reporter Film and TV Music Conference:

Robert Duncan appeared as a featured speaker on the “Composing for Series Television” panel.

Trevor Morris is a featured speaker on the panel titled “Halloween, Horror, and Hollywood”.

Toronto Ravel:

John Herberman led the inaugural orchestration study group in the study of Ravel’s ballet Daphnis and Chloe with special guest Ron Jones.

AWARDS

Emmy Awards:

Mychael Danna won his first Emmy Award on Sept. 15, 2013, for the mini-series World Without End, in the category of Outstanding Music Composition for a Mini-Series, Movie or a Special (Original Dramatic Score).

Other SCGC composers nominated include Trevor Morris The Borgias: The Prince and Robert Duncan The Last Resort: The Captain in the category of Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score), and Yuri Gorbachow Vikings: Trial for Outstanding Sound Editing for a Series.

SOCAN Foundation Awards for Young Audio-Visual Composers:

Chris Thornborrow was lauded for his “understated but tension-laden score” for We Ate the Children Last, which won the $3,000 first prize in the Fiction category. His score for Lucian won the $1,500 second prize in the Animated category.

CFC Slaight Music Residency:

Erica Procunier and Rob Teehan have been selected as the 2013 composer residents.

SCREENINGS

Atlantic Film Festival:

Craig McConnell and Erica Procunier The Golden Ticket

Festival des Films du Monde – Montreal International Film Festival

John Welsman Momsters Playground

Toronto International Film Festival:

Mychael Danna Devil’s Knot

Steve Cupani Silent Garden and Darren Fung Winter Garden and The Archivist, special TIFF screenings celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatres

Todor Kobakov The Husband

Toronto Independent Film Festival:

Chris Pauley Roaming, which won Best Feature Award

Ralf Cassidy Bindels Tree Line

Janal Bechthold Manfred and the Waiting Room, which also picked up first prize for short film at Festival Internacional de Cine in Puebla, Mexico.

Ottawa Animation Festival:

Tristan Capacchione Blackout, which received an honourable mention in the Canadian Student Showcase program.

Vancouver International Film Festival:

Brent Belke I Saw You

John Welsman Hue: A Matter of Colour

Kenton Gilchrist Anxious Oswald Greene

Edmonton Film Festival:

Brent Belke I Saw You

Blood in the Snow Film Festival:

Luc Arsenault The Basement

Caribbean Tales Film Festival:

John Welsman Kingston Paradise,

Audience Choice Award

Toronto Animation Arts Festival International:

Meiro Stamm created music for the 2013 sponsor reel and pre-screening bumpers

TELEVISION PREMIERES

Beyblade Metal Fury (YTV) Neil Parfitt

Border Security Season 2 (NatGeo, Global) Greg Fisher and Derek Treffry

Castle Season 6 (ABC) Rob Duncan

Cracked Season 2 (CBC) Rob Carli

Dracula (NBC) Trevor Morris

Hunt For the Labyrinth Killer (Lifetime) Jeff Toyne

Murdoch Mysteries Season 7 (CBC) Rob Carli

Oh No! An Alien Invasion (YTV) Neil Parfitt

Out With Dad Season 3 (Web) Adrian Ellis

Played (CTV) Tom Third

Real Potential (HGTV) Greg Fisher and Derek Treffry

Tom, Dick, and Harriet (Hallmark) Brent Belke

From the Editor

This issue of Spotting Notes has addressed many challenges facing screen composers – and, indeed, all content creators – as our industry continues to adjust to new distribution paradigms. Here are some relevant links to additional articles and content:

New Report: Building the New Business Case for Bundled Music Services

http://musicindustryblog.wordpress.com/author/musicindustryblog/

Billboard: Composers Seek Change in Copyright Law

http://www.billboard.com/biz/articles/news/publishing/1269445/composers-seek-change-in-copyright-law

ASCAP: What Music Creators Should Know About Streaming Royalties

http://www.ascap.com/playback/2013/01/wecreatemusic/what-music-creators-should-know-about-streaming-royalties

For anyone interested in more information about the Status of the Artist Act, under which the SCGC is certified, here is an informative article from the Canadian Journal of Communication:

http://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/939/845

![]()

We welcome your feedback and suggestions for story ideas!